Chapter Two: The Galactic epoch

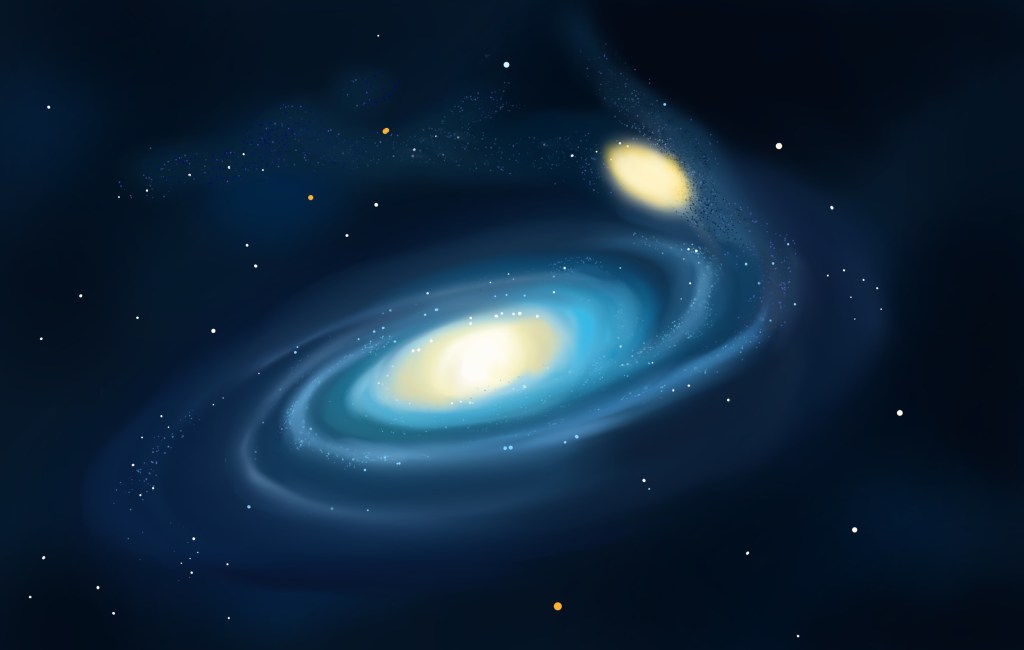

Galaxies Start to Spiral

11.7 Billion Years Ago

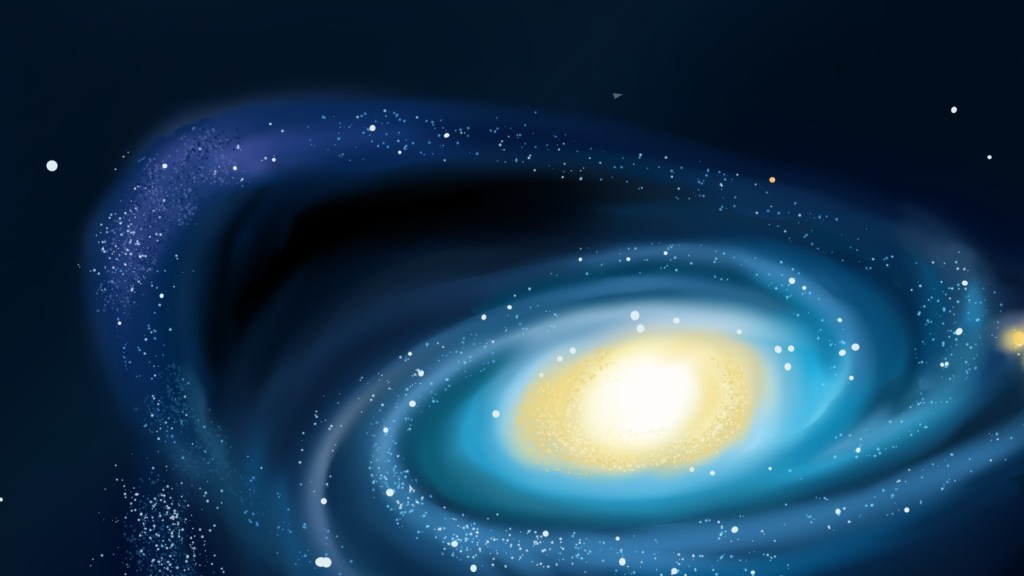

The effect of gravity continues to shape celestial entities like our very own galaxy. This shifting of gravity can also have smaller effects. Mineralogy of meteorites from Earth gives us 250 different minerals in a variety of meteorites, because we know what materials were present in the local stars, we can tell that these minerals likely came about from the forming and fracturing of planetesimals. Clays, Mica, and Zircon all become the building blocks of Earth and other rocky planets. At the very least in our section of the milky way, the Orion Arm, our very own spiralised arm address.

The Milky Way merges with Gaia Enceladus

11 Billion Years Ago

A galaxy dying is called quenching, where the process of star formation is shut down either through removing (internal process) or heating (external processes) the gas. Coalition is when galaxies merge, causing the opposite effect due to the introduction of more matter. More stars and celestial objects can then be created, increasing rather than reducing star activity.

I’m not joking when I say this dwarf galaxy is called The Sausage or Gaia Sausage. You’ve got to love scientists, inside every scientist is a failed poet having an aneurysm. It gets this name because of the shape of the star cluster that is theorised to have once been the Gaia Enceladus Galaxy. These stars are very old and at the edge of the Milky Way.

Peak Star Formation within the Milky Way

11 to 9.8 Billion Years

This may have happened because of the galactic coalition between The Milky Way and Gaia Enceladus, the resulting turmoil of gravity and introduction of more gasses and dust lead to there being an increase in stars, estimated to be about 10 times higher than it is today. Because the stars within our galaxy are that much closer we are able to determine their age a lot better, and because we know about the various interactions our galaxy has with other celestial objects it helps us determine what caused these fluctuations in star formation.

Earliest Estimation Of Dark Energy

9 Billion Years Ago

This is not the same stuff as dark matter. Dark matter’s effects have been observed since ~12.094 billion years ago and has likely always existed in some capacity, whatever it may be, but that is a scholastic rabbit warren I’ve already touched on. Dark energy on the other hand may have come about later. To find something that you cannot see you have to look at how space-time and celestial objects react. The effect that dark energy has on matter and universe structure is the only evidence that it exists. Seemingly having the opposite effect of gravity, pushing matter away rather than drawing it in. So, another increase of expansion 9.8 billion years ago, maybe due to an increase of whatever dark energy is.

Dark energy probably isn’t just one component. It currently takes up about 68.3% of the entire mass of the universe, acting like a cosmological constant, meaning that gravity and matter have a larger effect in the beginning, but their effects slowly diminish over time while dark energy remains consistent, indicating that dark energy probably predated 9 billion years ago, but its effects didn’t start being observed until then. Earlier estimations currently are being made as we get more data from cosmological surveys.

Currently, the cosmological survey maps out the percentages of out universe thusly; 68.3% is Dark energy, which may be a force more than matter and likely isn’t just a singular thing. 26.8% is Dark Matter, which could be a flaw in our models of gravity, new types of particles or both and 4.9% is Baryonic Matter, objects that we can observe and that absorb or emit light. And all of those figures hinge on our assumption that some simple equations that are currently being stress tested and found to be slightly lacking were entirely correct. Just as our understanding of species and where the arbitrary line in the gradient is drawn has changed so will our understanding of matter and particle physics, because science is not static and hopefully never will be.

The Milky Way’s Disk Becomes inactive

The amount of gas available in the disk has been depleted and the disk stops actively creating new stars.

Universe Cools Below 5 Kelvins

7.1 Billion Years Ago

Temperature is important. The rate of cooling is a useful data point. Using the laws of physics, our understanding of particles, and how they behave in certain conditions, we can predict what temperature the universe is. Kelvins are the closest we can measure to absolute zero. Celsius uses the point water freezes and Fahrenheit uses the basal temperature of the human body, both using degrees to indicate their relation to kelvin. It is a scientific measurement meaning it’s used internationally, giving clarity to scientific papers and a basis for thermodynamic temperature. Lower temperature means that particles will behave in the ways they currently do, which is why this measurement of energy is worthy of mention when structuring a timeline of the universe.

The Rate of Expansion Increases Again

6 Billion Years Ago

Yeah… it ain’t slowing down. You may think it’s a long way to the shops, you may think the universe is bigger than you can comprehend. It’s getting bigger. Dark Energy reaches 33% of matter in the universe at this point, possibly causing the acceleration. Over the next 6 billion years it will increase further to approximately 68.3% It’s still a mystery exactly how and why this happens.

The Milky Way collide with Sagittarius dwarf

6 to 5 Billion Years Ago

We know a little more about this collision than the first. We also know that Sagittarius Dwarf and the resulting fragments collided with the Milky Way multiple times. Parts of it can still be seen in the far reaches of the galaxy, and will likely collide again. There are so many types of celestial bodies within the Milky Way, planets come in many varieties. Tidally locked planets; where one side is always in starlight, the other in darkness. Occurring when the rotation of a planet matches its orbit around its star. Hot Jupiters; Gas giants that orbit close and fast to their suns, usually completed within five days. As a result they are extremely hot, forming cloud droplets made from molten glass and high wind speeds. There are moons with cryovolcanism such as Miranda, Titan, and Ganymede. All of which are found in our solar system. Enceladus is a planet with sub-oceans under a 60-kilometre ice sheet. Our astronomical ecosystem is varied and wondrous, these collisions were probably the cause of an explosion of star formations, which included our own yellow giant, the Sun.

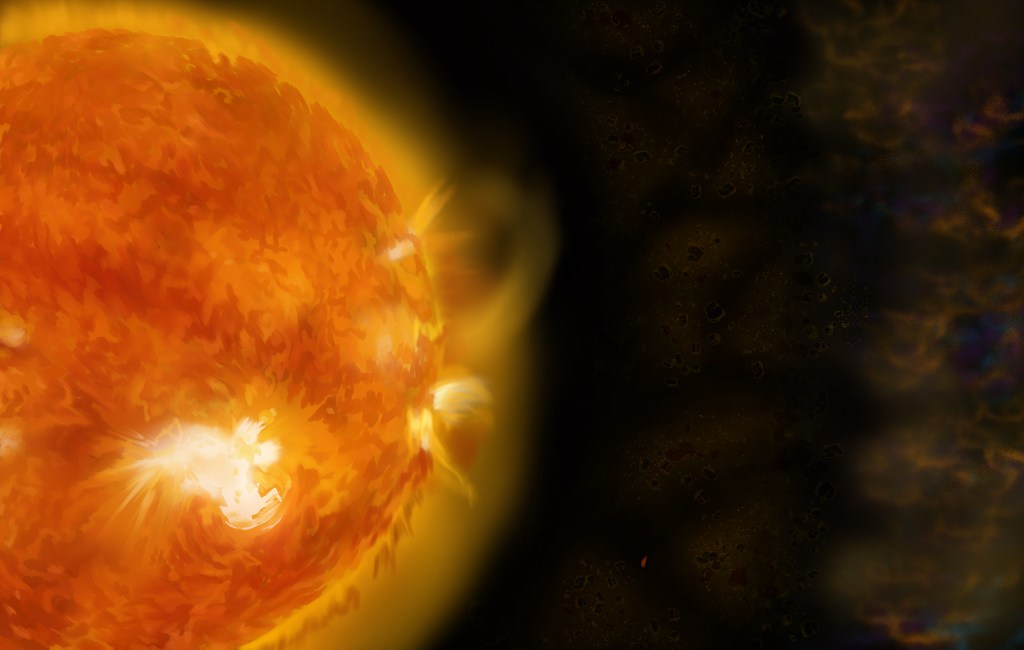

Our Sun Forms

4.6 Billion Years Ago

Our Sun is a late-generation star, incorporating the debris from generations of earlier stars, this newly formed stardust began to clump together, gravity steering these clumps into clusters of rock, falling into orbit around the newly formed Sun. Moulding into the planets, asteroid belts and moons we know today. Welcome to our solar system.

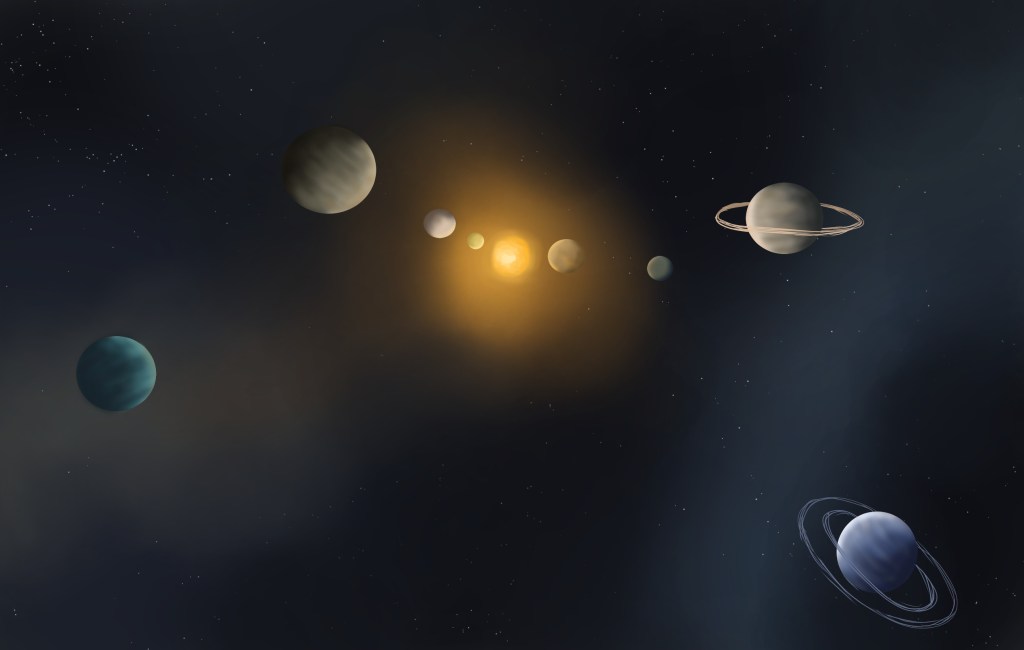

Our Solar System

Some solar systems have multiple stars, the most common in our galaxy are double star systems, but there are triple systems as well, and in just one of these solar systems we have our home. The rocky inner planets Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars formed when intense pulses of solar winds separated hydrogen and helium from the heavier elements, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen phosphorus and sulphur, sweeping the lighter gaseous elements outwards to the domain of the giant planets, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. The same separation effect can be seen in the structure of Earth, heavier molecules collect and settle at the centre, forming the metal-rich core. There are of course more details that brought the Earth’s structure as we know it into being.

For The Curious

Books

Bryson, B. (2016) A short history of nearly everything. Random House UK.

Smethurst, B. (2020) Space at the speed of light: The history of 14 billion years for people short on time. California: Ten Speed Press.

Papers

Morabito, L.K. et al. (2022) “Sub-arcsecond imaging with the International Lofar Telescope,” Astronomy & Astrophysics, 658. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202140649.