Brought to you by the noble Cnidirea. Specialist amongst the classy Hydrozoa. A jellyfish that is not quite a jellyfish, to be a jellyfish is to forever be alone. The order of Anthoathecata, much like many of the world’s most powerful countries, has a colonial stage. From the sunless depths of tropical seas come the secrets of immortality. Sort of.

Seven Ages of Oceaniidae Jellyfish

First you must become aquatic, no I don’t mean this half-arsed nonsense mammals do. Cetaceans, Pinnipeds, all beasts who are lacking; Stuck with a closed circulatory system, a bilateral body plan, and a brain. If you intend to live forever simplicity is key, as is living interestingly and doing so many times within a life span. Hence your new life cycle being… varied. Throw your circulatory system away to waste. Weave your simple nerves together, making a neural net to replace this strange and uncommon brain. Brains are for the mortal. Become a 4.5mm, spherical, radially symmetrical invertebrate. If you already be small, fierce, circular and became less sociable during adulthood, you’ll fit right in.

So, what will await you in this new life? All the world, is after all, a stage. All its oceanic fauna merely players. They have their exits and their entrances, and some species in a time may play many parts, their acts being the seven ages.

Our mewling infant is replaced with a fertilized mass of cells, the perfect reproduction for those who have commitment issues. Children without the childbearing and sexual reproduction without the sex.

The whining schoolboy, becoming Planula, larval in form. Its cilia moving and modulating ‘till meeting the pelagic floor. Attaching and unwilling to move from its substrate home.

And then the polyp. No lover nor ballad, but branching chitinous tubes made in its sessile state. Unmoving and anchored by stolons.

Then a hydroid.Full of strange zooids and hollow branches, extending from a body made up of so many lives. Polyp in form. No quarrel, but unity as a colony in function.

If thou wants to live forever thou cannot go through the polyp stage alone. Non-polymorphic, Gastrozooids and dactylozooids; two such life forms that make up this collection of creatures housed as one and act as one, reaching for drifting plankton and falling marine snow.

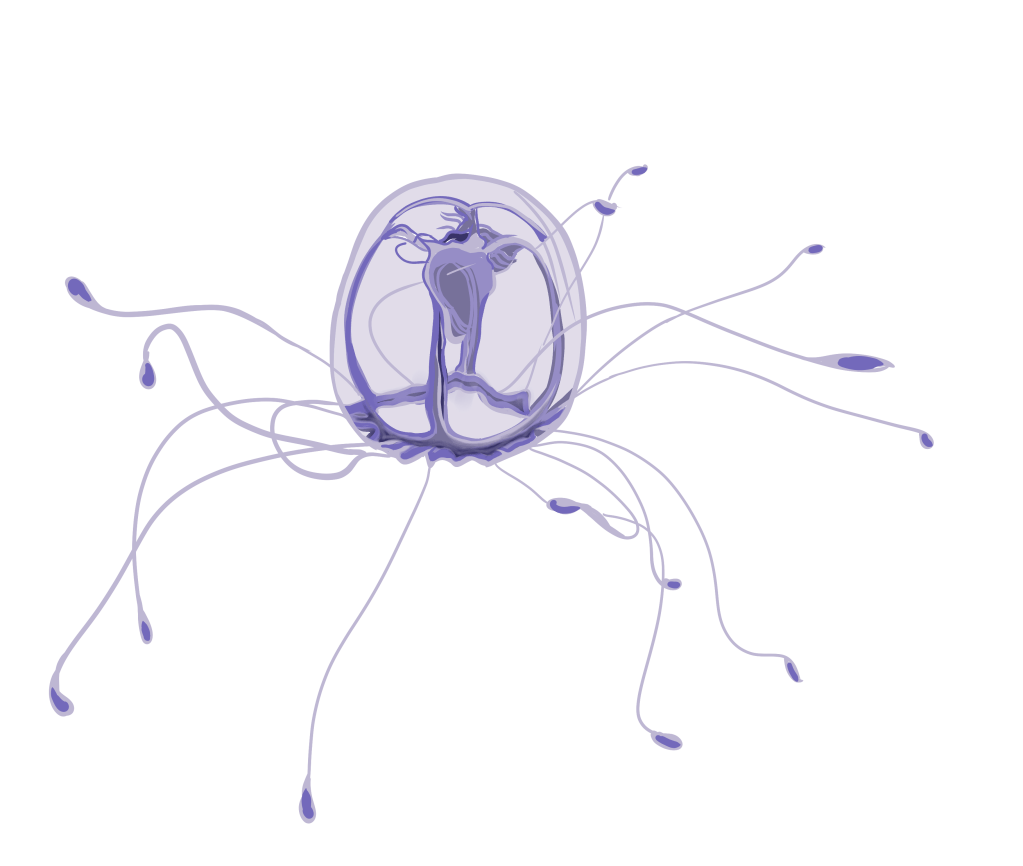

And then the budding phase. Gonophores form from polyp bases, asexually reproducing hundreds of diploid immature medusas. Neither wise nor modern. And so it plays its part.

The 6th age shifts, into the lean and lesser tentacled immature medusa. With bell-shaped mesoglea and stinging nematocysts in cnidocils. Unlike the humans who observe it, this is not the age of a voice turning again to childish tremble, but of possibilities.

Last seen of all that ends this strange and eventful history is mature medusas or perhaps regression into second childishness. Because of course, forTurritopsis dohrniithis is not the end. You need not fear oblivion.

Sans everything, including my sanity. You lack teeth. You lack taste. You barley have eyes. Your body, bell, tentacles, etcetera breaks down, reverting back to a polyp.

Or thine mortal flesh breaks down in the inevitable process of being torn apart by predators or possibly being worn away by the decay of senescence, we’re unsure whether the little dohrnii that you are can continue this ontogeny reversal indefinitely.

Let’s assume thou shall live forever. Although I cannot guarantee thou shall love forever.

The oddity of ontogeny reversal

Ontogeny reversal via trans-differentiation. Rolls off the tongue dose it not? from polyp to medusa to polyp again. That thick epidermis of thine medusa will protect the soft gelatinous mesoglea within, but not from all and everything. What of the climate change fuckary with ocean temperatures and tempests? What of prolonged famine? Thou art not a barn owl, thou cannot eat thine siblings. This my dear squishy is where thine witchcraft and trickery o’ common folk comes in. Let us take thee back to a teeny tiny polyp. It shall result in thou going through the jellyfish equivalent of puberty again. Twice. And backwards. And forwards. This here word wrangler never claimed living forever would be easy.

Cells from thine medusa dedifferentiate, regressing from specialised cells to stem cells, then re-differentiate once again into relevant polyp cells. T’is the same flesh, the same tissue, merely a different order. Thine mesoglea, now stuffed up inside thee. Emerging once again as an immature medusa. A familiar form of a jellyfish. Well, many forms, many copies. Learn to like thine own company, it makes life much more enjoyable as one of a brood of clones.

Okay, technically this immortality is regeneration. Doctor Who is a Turritopsis dohrnii, you heard it here first. “Regeneration jellyfish” doesn’t sound as mystical, and Cnidaria are so often considered boring. We work with what we have. And what we have is Shakespeare and functional immortality. Public representation is important, so give half-truths whenever necessary, it makeththou more interesting and endears thee to the people. Scientific accuracy be damned.

So now, as an intriguing gelatinous blob, when things get bad, when thy environment sucks, thou can regress into polyphood be born anew and live again. Unless thou geteth eaten, no coming back from another organism’s digestive tract I’m afraid.

Do this right and scientist will sing your praises. Be mindful of this thing called time though, “time is a drug. Too much of it kills you.” Eventually.

Until next time wonderful reader. Have a nice day and have a great life.

For the curious

Cartwright, P. and Nawrocki, A. (2010). Character Evolution in Hydrozoa (phylum Cnidaria). Integrative and Comparative Biology, 50(3), pp.456-472. doi.org/10.1093/icb/icq089

Kubota, S. (2009) Turritopsis sp. (Hydrozoa, Anthomedusae) rejuvenated four times. Bulletin of the Biogeographical Society of Japan 64, 97–99).

L. Martell, S. Piraino, C. Gravili & F. Boero (2016) Life cycle, morphology and medusa ontogenesis of Turritopsis dohrnii (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa), Italian Journal of Zoology, 83:3, 390-399, DOI: 10.1080/11250003.2016.1203034

Piraino, S. et al. (2004) Reverse development in Cnidaria. Canadian Journal of Zoology 82(11), 1748–1754

Schmich, J., Kraus, Y., De Vito, D., Graziussi, D., Boero, F. and Piraino, S., 2003. Induction of reverse development in two marine Hydrozoans. International Journal of Developmental Biology, 51(1), pp.45-56. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.062152js

Schmid, V. et al. (1982) Transdifferentiation and regeneration in vitro. Developmental Biology 92(2), 476–488.