Not all 17 species of penguins are acclimatised to the Antarctic. They won’t tolerate it, like it, or help you. But a few of these amazing avians, these fascinating Spheniscdae of the southern hemisphere, call the cold home. So, fellow humans, who prefer cold over cooking, I give you the fascinating physiological and anatomical tricks of the Aptenodytes genus.

Colours Palette

Lesson one: limit your colour palette. With maturity comes camouflage and sophistication. Showing that you are a functional member of society and, with countershading, you’re able to sneak up on fish and stay safe from seals. If you truly wish to emulate the enigmatic Emperors of the ice you could use the unique microstructures of the blue and yellow feathers. Exclusive to penguins, and as any fashion-oriented Homo sapien knows, exclusivity is synonymous with wealth. You as a human can use dyes for this effect. I suppose. For a penguin adding colour puts a cost on their metabolism, they aren’t like other avians you see, Spheniscdae can synthesise yellow by themselves, the pigment is formed from amino acids called spheniscine with no assistance from consuming carotenoids. This tells other penguins you can afford the splash of colour both at a metabolic level and at a fitness level as this makes you more obvious to predators. Although yellow doesn’t travel far in water, and we’re in the Antarctic, no polar bears of foxes here.

Most birds have eyes that behold the beauty of Ultraviolet. Emperor (Aptenodytes forsteri) and king penguins (Aptenodytes patagonicus) are no different. Explore colours that your species can see, but be particular. Layering reflector photonic microstructures means interactions with different light frequencies occur. The ultraviolet markings themselves seem to merge membranes, forming elaborate folding microstructures. Intervening filaments of β-keretine give a rippling effect on the under-bill. Which not only sound impressive but also turns your body is artwork. For mature penguins, the hues increase, incidentally indicating this is a form of sexual signal. No tasteful rave markings until you’re legal drinking age.

Layers

Lesson two: Layer up and layer smart. Colours are important, but countershading and sexual signalling will mean nothing if you’re dead. Turns out -40°c (-50 for emperors) is cold. And although your mother may tell you to put another jumper, the more layers you have, the heavier the load, the more energy you have to expend. There’s also the streamlining issue. marsh-mellows aren’t good at catching fish. I’ve learnt the hard way. Be economic with your layers.

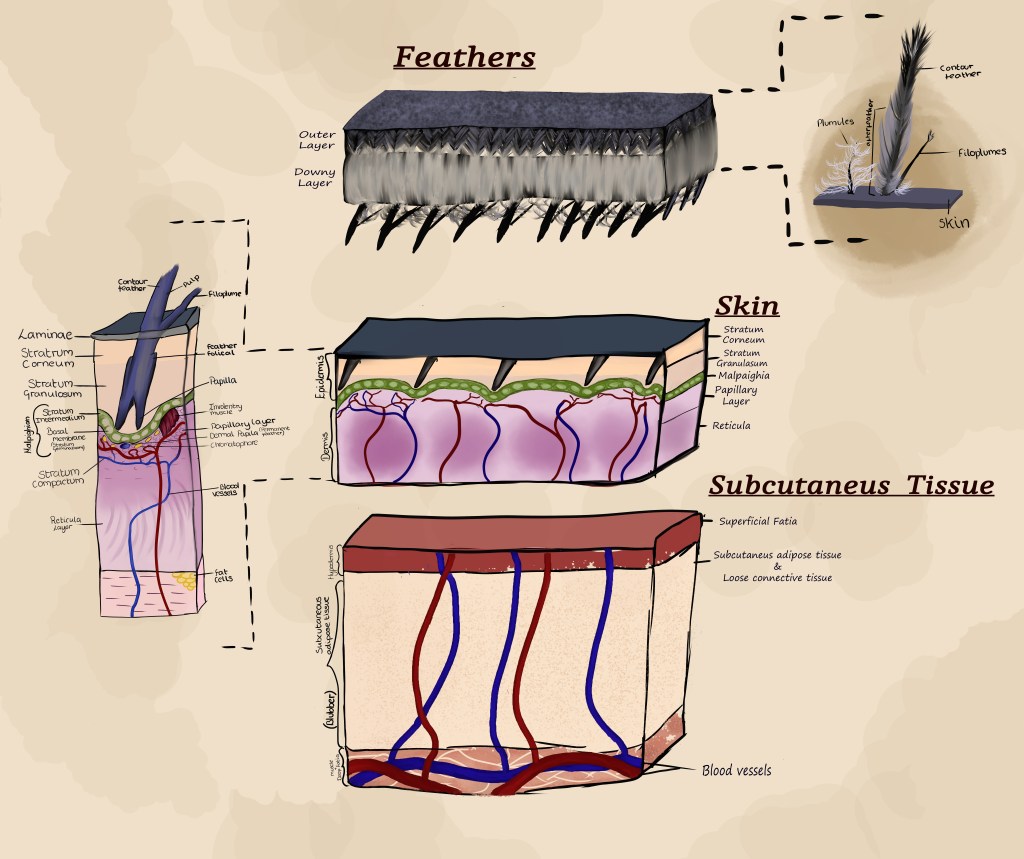

Start with subcutaneous adipose tissue (blubber). Especially before breeding season. Mates will be found, eggs will be laid, chicks will be fed and catastrophic moulting will occur. All of which takes up a lot of energy. Some fantastic feathers will also help you save on heating, twelve different types of feather under three categories to be exact. Blending is best.

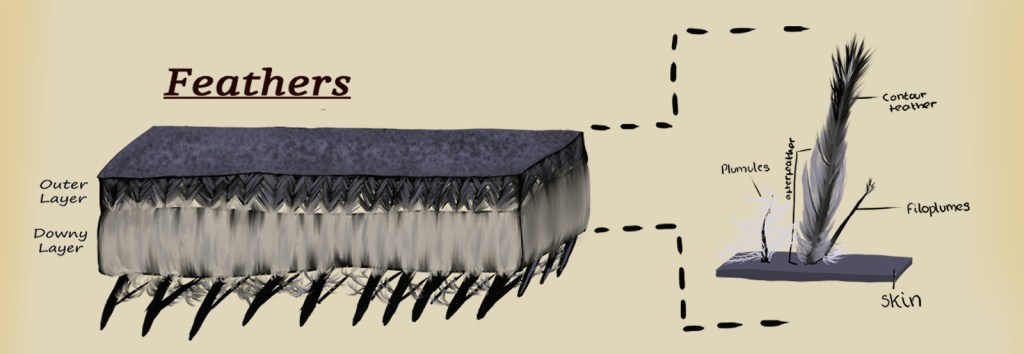

First, there is the finest of filoplumes, these small attachments to the contour feathers make for an excellent base layer. It’s also possible that they help penguin adjust and maintain their feathers through sensory signalling, but these secrets of sea dwellers have not yet been confirmed. The contour feathers themselves are stiff, (aiding hydrodynamics), oily, (for the waterproofing), and where all the colour is, (to aid looking fabulous). The afterfeather, together with the adjacent but separate plumules, make up the insulation layer. Your amazing Aptenodytes self has substance, style and function.

Penguins are apparently not as dense as we thought. They focus their feathers around their core, 29% to 50% more around their chest than their dorsal. But it’s the spatial organisation that matters, not feather count. Each contour and attached filoplumes have approximately 9 surrounded by plumules. Hence why the dapper dipper (Cinclus) has a higher density of contour feathers but will never be a king or an emperor when it comes to plumules.

Don’t Get Frostbite

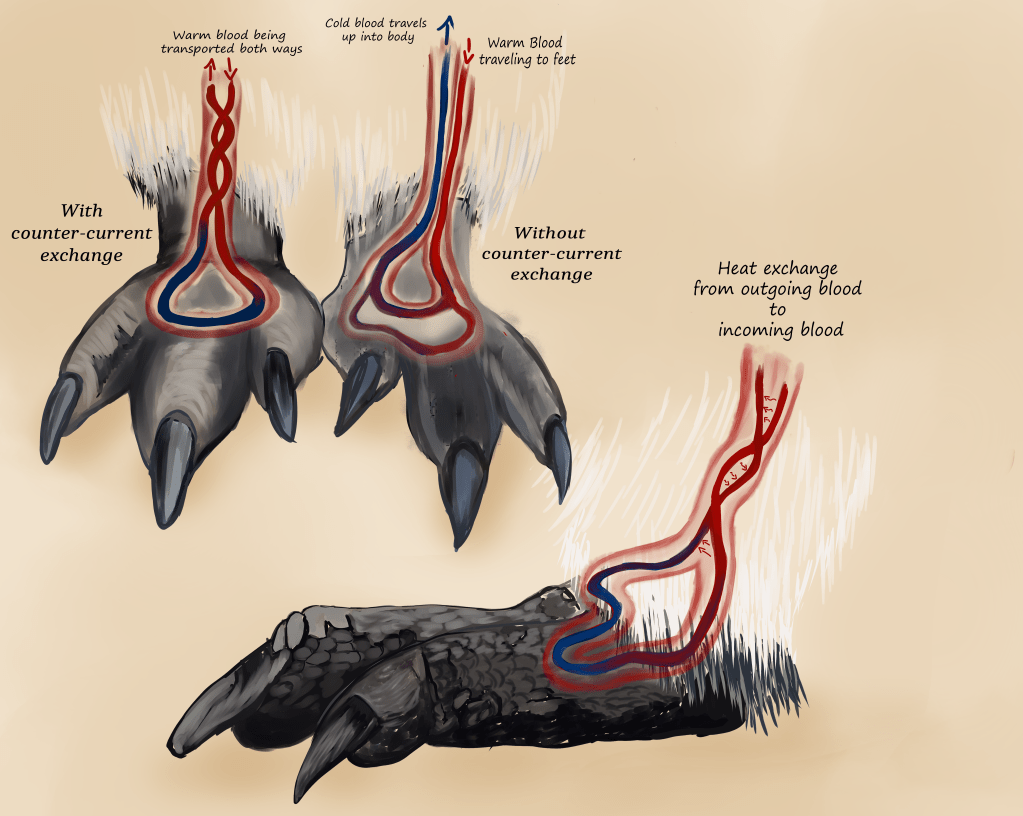

Lesson three: human circulation is lacking, be a penguin. Frostbit doesn’t look great. Which as we know is the worst thing a human could ever experience. Layers of skin and underlying tissue freezing also isn’t great for your health. Funny that. So, look great and feel less frostbitten without sacrificing hydrodynamics with an all-new(ish) circulatory system. Especially for the parts that aren’t covered in feathers, because you’re a damn penguin and refuse to wear shoes.

There’s a certain saying from a book of Wintersmiths, “If you want something done, give it to someone who’s busy.” A penguin’s body is a busy place. Efficiency and laziness is key. Cold blood from the feet can ruin the delicate equilibrium of homeostasis. Penguins entwine the accusatory veins with warmer veins from the heart, enabling the transfer heat, that will be lost anyway, to the cold veins. Counter-current heat exchange ensues the feet are fed just enough warm blood to stay above freezing. Thermal convection will deal with the rest. Keeping the outer layer of feathers cold, while the skin and downy layer are warmed by the body creates small waves of convection currents between the cold outer layer, enabling penguins to absorb back some of the cycling heat that’s being lost through the feathers before it cycles away again. Like waves depositing pebbles on a beach. I’ve come over all poetic, so to counter this.

Embrace Catastrophe

Lesson four: accept your fate. Embrace that you will look like shit, feel cold and stare into the void for a week. Penguins call this a catastrophic moult. Everything is a mess, you can’t do anything about it, you probably won’t die. You’ll emerge warm, reformed and even in the coldest, darkest, most wintery places on the planet, you’ll look good. You’ll live well. You’ll also get walloped by the metaphorical anvil of climate change. So good luck. With your layers and a colour pallet to die for, you may not dream of being Al Capone, but you may end up smelling of a dry fishbone if you’re stone-cold and crazy. Like a penguin.

Until next time lovely reader. Have a nice day, and have a great life.

For The Curious

Dresp, B., Jouventin, P. and Langley, K., 2005. Ultraviolet reflecting photonic microstructures in the King Penguin beak. Biology Letters, 1(3), pp.310-313. DOI: 10.1098/rsbl.2005.0322

Ksepka, D.T., 2016. The penguin's palette--more than black and white: this stereotypically tuxedo-clad bird shows that evolution certainly can accessorize. American Scientist, 104(1), pp.36-44.

Kulp, F.B., D'Alba, L., Shawkey, M.D. and Clarke, J.A., 2018. Keratin nanofiber distribution and feather microstructure in penguins. The Auk: Ornithological Advances, 135(3), pp.777-787. Doi:10.1642/AUK-18-2.1

Williams, C.L., Hagelin, J.C. and Kooyman, G.L., 2015. Hidden keys to survival: the type, density, pattern and functional role of emperor penguin body feathers. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 282(1817), p.20152033. doi/10.1098/rspb.2015.2033

Mccafferty, D.J., Gilbert, C., Thierry, A.M., Currie, J., Le Maho, Y. and Ancel, A., 2013. Emperor penguin body surfaces cool below air temperature. Biology letters, 9(3), p.20121192. Doi:10.1098/rsbl.2012.1192